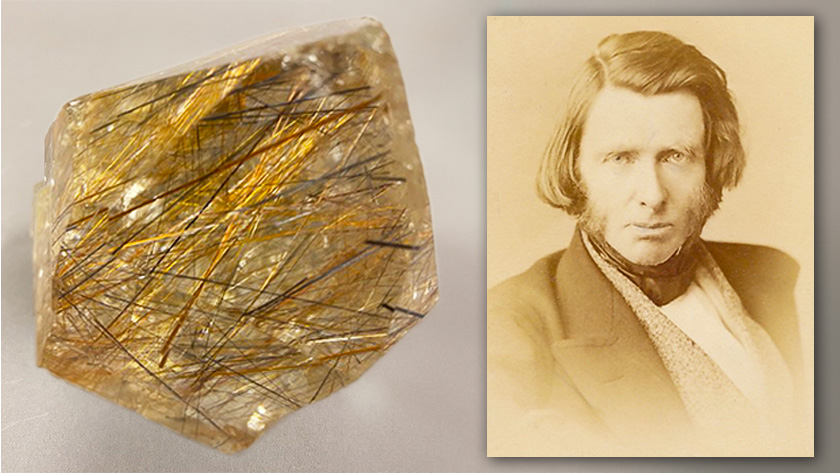

Left: Rutilated quartz. Right: Elliott and Fry, John Ruskin, albumen carte-de-visite, [1869]. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press

A View from the Vault: Rutilated Quartz from John Ruskin’s Collection

By Sharon Fitzgerald, Museums, and Mark Samuels Lasner, Special Collections

“A View from the Vault” showcases some of the unique, notable or rare items that are a part of the Special Collections and Museums holdings at the University of Delaware. Each month, we highlight a different item and share interesting facts or intriguing histories about it. If you are interested in seeing any of the materials featured in person or want to learn more about anything showcased in the series, please contact Special Collections and Museums at AskSpec or AskMuseums.

Rutilated Quartz

Rutilated Quartz

Switzerland

Mineralogical Museum Permanent Collection

Numbers matter and sometimes bring surprises. The number 107 is written on the back of this exceptional specimen in our collection. Originally believed to be of California origin, the quartz was re-examined after the curator of the Mineralogical Museum read an April 1925 invoice of specimens offered to the museum’s founder, Irénée du Pont, by the dealer Wards Natural Science Establishment. The Wards list identified the mineral as a rutilated quartz from Switzerland: No. 107 from the collection of John Ruskin – a distinguished provenance, if true.

John Ruskin (1819–1900) was not only the foremost art critic in Victorian Britain — famed for his books Modern Painters (1843), The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and The Stones of Venice (1851) along with his 1878 legal dispute with the American painter James McNeill Whistler — but a social reformer, a talented artist and, most importantly in this context, a lifelong enthusiast for “rocks.”

Ruskin wrote continually about geology, amassed a personal collection of more than 5,000 mineral specimens, and donated sizable collections to multiple institutions. For him, mineral specimens were “mountains in miniature” — crucial to the study of geology as well as touchstones of the earth and landscape. Returning frequently to Switzerland, the source of our quartz, he often visited Chamonix at the foot of Mont Blanc, where he noted the impact of climate change on glacial erosion.

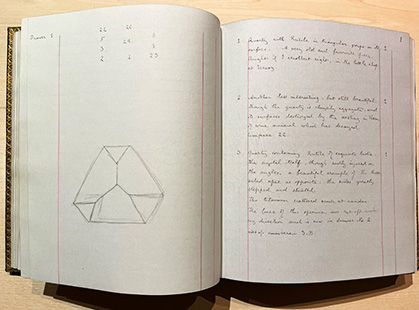

Confirmation of the specimen’s history came recently from British mineralogist Roy Starkey, who informed us that the label next to the handwritten number 107, which shows a “3” over an “R,” is a known Ruskin label and thus further proof. In fact, Ruskin sketched and described this specimen in detail in one of the manuscript catalogs of his collection held at Brantwood, his Lake District home.

John Ruskin, 1819-1900. Catalogue of minerals, Vol. 3, 1884: autograph manuscript. John Ruskin Mineral Collection, Brantwood

According to Starkey, the UD specimen is one of only four outside of Europe that he has found so far. The rutilated quartz specimen complements a wealth of Ruskin materials in Special Collections, including autograph letters, drawings, signed books, volumes from Ruskin’s library and portraits in the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, and serves as a reminder of his love for the natural world.