Digital Delaware: Texts on the Political History of Delaware Published by UD Press

By David Cardillo, Digital Initiatives and Preservation

While one of Delaware’s nicknames, Small Wonder, may be apropos, another nickname, the First State, suggests a state rich in history, extending back to colonial days.

Fortunately for scholars and even amateur historians, there are plenty of free, digital resources on this diamond mine of history (the Diamond State is another Delaware nickname). One such set of digital collections is the digitized UD Press backlist titles. Since 1923, the UD Press has given voice to the history and culture of the Delmarva area in addition to providing a wealth of knowledge on many other topics, such as literary studies and art history.

One example of the historical culture of Delaware would be Dutch and Swedish Place-Names in Delaware (Dunlap, 1956). In the very early days of the settlement in what is now Delaware, there was much volleying of ownership between England and Sweden. Some place-names changed according to whichever political power was dominant at the time, and some of the place-names eventually became permanent, regardless of which country was in charge, and exist to this day, such as Governor Printz Boulevard.

Delaware Becomes a State (Munroe, 1953) is a small publication, but gives a nice synopsis of the colony’s involvement with the Revolutionary War, then establishing a state constitution and economic infrastructure that allowed Delaware to metamorphose from colony to first State of the Union.

Drawing of a Delaware Private in the Continental Army, c.1776 (Delaware Becomes a State, 1953)

As told in John Spruance’s Delaware Stays in the Union (1955), the next major war in Delaware history was the American Civil War. While no battles were fought on Delaware soil, citizens from Delaware fought on both sides of the war. Delaware itself was deeply conflicted regarding the war, for while Delaware did not secede from the Union, secession was constantly debated and Delaware troops often rooted out and arrested Confederate sympathizers.

From Delaware Stays in the Union (1955)… Drawing is from a scene of soldiers arresting picnic attendees.

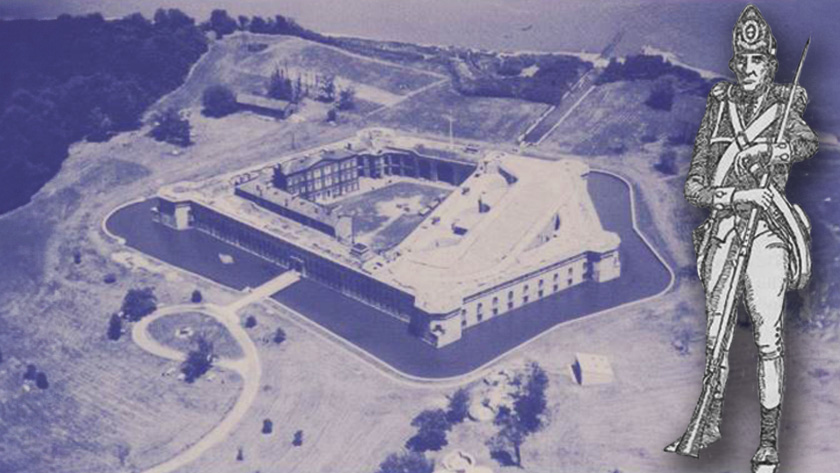

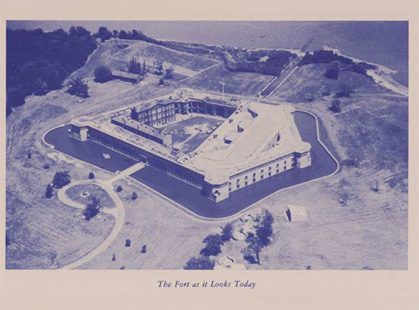

Speaking of Fort Delaware (Wilson, 1957), there is another small publication about the history of the military installation, focusing primarily on its use as a prison for Prisoners of War during the American Civil War.

Fort Delaware at Pea Patch Island, c.1957

Fort Delaware unfortunately is infamous for the poor conditions in which its prisoners were kept. The book details how the fort had not been designed for mass incarceration of prisoners of war, and was inundated with more prisoners than it could possibly have held even if it had been designed as a POW facility.

These texts and more provide a vivid snapshot of Delaware’s role in the rise of the United States as a nation, and its survival of an internal conflict, and other University of Delaware Press texts not mentioned here show Delaware’s role as America became a world power, such as The American Clyde (Tyler, 1958), a book about shipbuilding facilities along the Delaware River from 1840 to World War I). There are also books in this collection pertaining to education, such as The One-Teacher School in Delaware (Cooper and Cooper, 1925), Negro School Attendance in Delaware (Cooper and Cooper, 1923), Plain Talk From a Campus, by University of Delaware President John Perkins (1959), and National Education in the United States of America (Du Pont de Nemours and Du Pont, 1923).

In conclusion, there is still a sizeable smattering of topics within the digitized collection of books published the the University of Delaware Press beyond socio-political topics. As copyright on titles expires and those titles enter the public domain, this collection will continue to grow, providing an even richer snapshot of Delaware’s growth and increase of importance over the past four hundred years.

The University of Delaware Press supports the mission of the university through the worldwide dissemination of outstanding, peer-reviewed scholarship in a wide range of disciplines in the humanities. The Press also publishes works on the history, culture, and environment of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of interest to the general public, enhancing the university’s community outreach. By supporting the creation of knowledge and serving the university as a source of information on scholarly publishing, the Press fosters the free exchange of ideas.