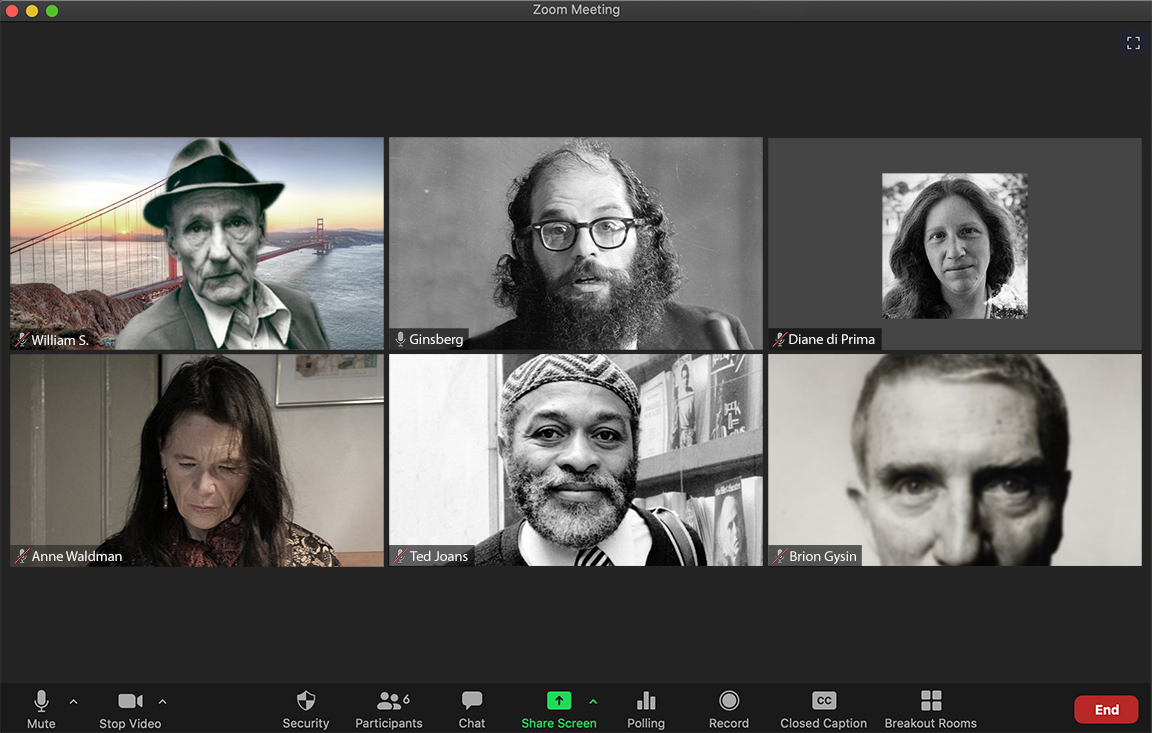

During this time of remote teaching and learning, many in the UD community have become familiar with Zoom, the online conferencing platform. Here, we imagine what a Zoom call between famous Beat authors and artists may look like.

The Beats at Home: Online Exhibitions for Learning and Leisure

Article by Allison Ebner | Graphic by Kris Raser

As we spend more time at home, many have turned to the arts for comfort, inspiration and discovery.

We stream movies and TV shows. We listen to music on live streams. We read books that have long sat on the nightstand. We use crayons, sidewalk chalk, colored pencils and watercolors to embrace our inner artists. We even venture into virtual gallery spaces to appreciate, explore and discover the works of others.

It’s true. While galleries and museums—including those on campus—may be temporarily closed, the culture, history and artwork they highlight remain accessible through online exhibitions.

With the digital version of the Beat Visions and the Counterculture exhibition, we can explore the ideas and imagery of the experimental, boundary-pushing Beat Generation and its influence on the 1960s counterculture. From the comfort of home, people have the opportunity to engage with rare and one-of-a-kind items related to the Beat movement—think handwritten notes, personal snapshots, poster art and even a beard clipping—previously on view in Old College Gallery.

While the online exhibition allows anyone to enjoy a dose of culture during the pandemic, it also has enabled diverse learning opportunities for students to engage with material objects—opportunities that otherwise would not have been possible in a remote environment.

For the class The Queer 20th Century, an upper-level undergraduate course in history and women’s studies, Professor Rebecca Davis initially planned to bring her students into Old College Gallery for an in-person exhibition tour led by Ashley Rye-Kopec, curator of education and outreach for Special Collections and Museums.

“My goal [with incorporating the exhibition in the class] was to help my students think more broadly about where we can locate evidence of queer history—not only in books or in old newspapers or diaries, but also in various kinds of ‘public humanities,’ including the art world,” Professor Davis explained.

As courses transitioned online, she and Ashley reimagined how these goals could be achieved in a virtual learning environment and how her students could still meaningfully engage with artworks at a distance.

With the online exhibition as the base, Ashley created a 20-minute virtual walk-through video tailored for the class that Professor Davis posted on Canvas, the digital learning platform used for each course at the University.

“The digital exhibit for this particular installation is quite vast, and Ashley helped by identifying specific sections of the exhibit and objects of art for the students to focus on,” Professor Davis said.

As she guided students through the exhibition, Ashley also emphasized the value of primary objects as resources and the importance of critical thinking, two essential components of the accompanying assignment.

After watching the video, students worked in small groups to take a closer look at one of the object labels within the exhibition. Together, they discussed how the label text relates to the queer experience and how it could be modified to emphasize that perspective more fully.

“The goal of the assignment was to have the students critically think about the story being told, and to understand that the label is a form of interpretation and scholarship,” Ashley said.

As is true of all scholarship, it is often told through a specific lens—one perspective of a larger story. “This exhibition specifically explores connections between the Beats and the counterculture,” she added. “But that’s not the only story you can tell with these objects.”

Ashley also joined the class for a Zoom session. As they discussed specific artwork from the exhibition, she was there to guide them through their observations—an interactive element not possible with a recorded video alone.

Those observations included looking at the items in the exhibition as material objects. If you look closely, you’ll find these materials provide more information than you may notice on first glance.

Take, for instance, the iconic photograph of Beat author Allen Ginsberg at a typewriter—a photograph taken by Peter Orlovsky, Ginsberg’s lover. On the photograph, which has been identified as Orlovsky’s personal copy, you can see thumbtack holes that indicate how this copy was once used: as a personal photo pinned to a wall. While the photograph is now framed and displayed in an exhibition, the thumbtack holes indicate it was once an item that was lived with as so many of our own personal photos are today. A single, almost hidden detail like this can provide rich, new layers of insight into an artist, subject or specific work.

In such instances, online exhibitions prove particularly beneficial as they showcase the full artworks or objects, allowing you to see details you may not otherwise have noticed in the gallery because they were covered up by the frame or mat.

By encouraging the students to look at an item through the queer perspective and the material culture perspective, it underscores the fact that one item represents many stories.

For Professor Davis, the learning opportunity proved a success for her students. “… Through the remote version of the class session, students thought about the ways in which queer sexualities shaped the lives of the [artists] and appeared in their artwork, imagining new ways of writing interpretive labels that highlighted that queerness where it appeared,” she concluded.

“[Professor Davis and I] wanted the students to feel comfortable and to know how to handle themselves in an art space,” Ashley explained. “It’s especially important for the students to realize there are untold stories in these spaces that might be of particular interest to them.”

With the online exhibition, students and the broader community have the opportunity to explore and delve deeper into these stories that would otherwise be inaccessible while the gallery doors are closed.

Even when the gallery doors reopen this fall with a new exhibition on the artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler and his friends, the Beat Visions online exhibition remains a resource available to support your research or pique your cultural interests.