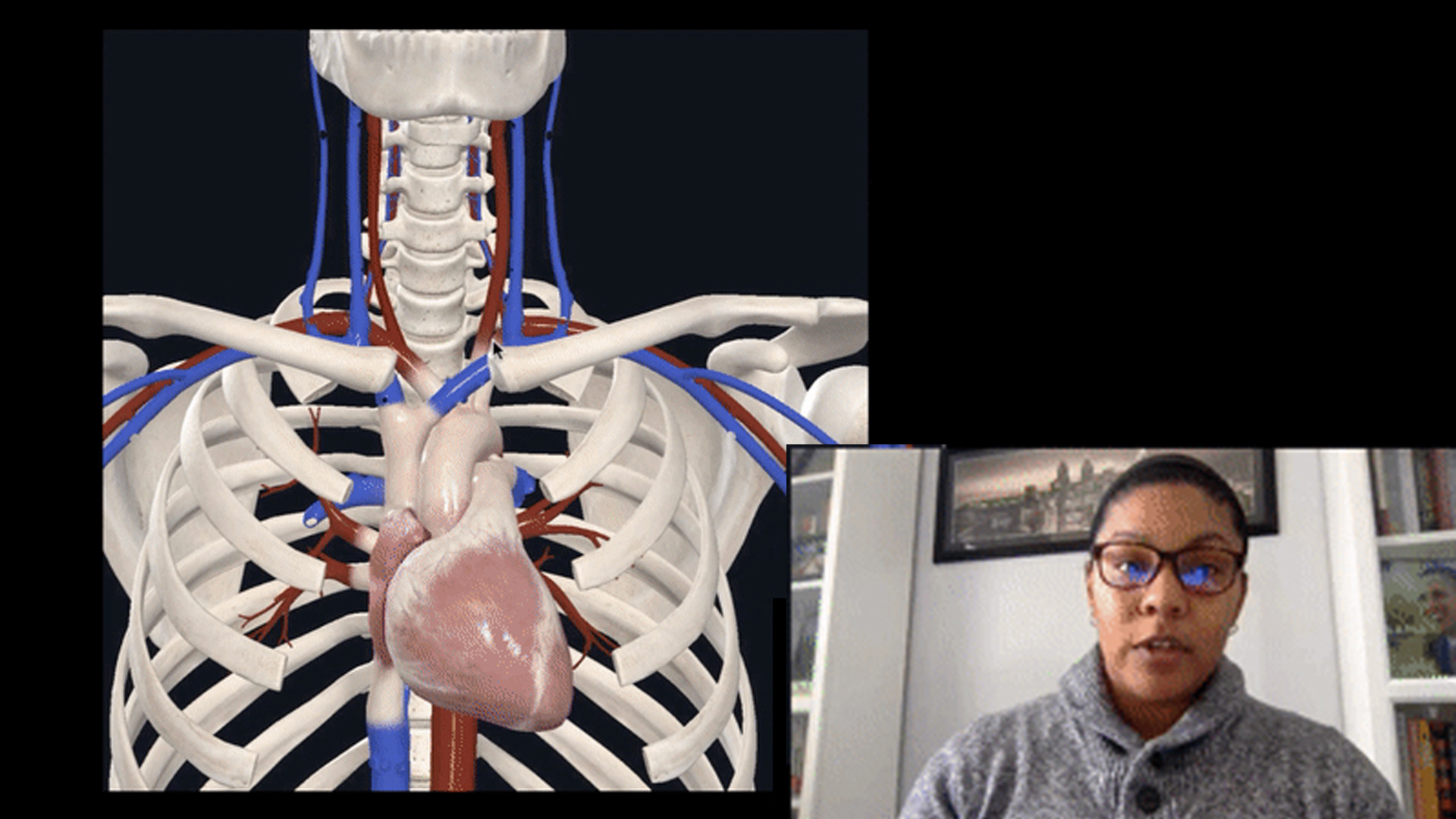

Professors Sheara Williamson (pictured) and Eric Greska transformed their course, Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology, using open educational resources that allow for the course and its materials to be more affordable, accessible and engaging. Here, Williamson is using the Complete Anatomy database to teach remotely.

Making Courses More Affordable and Accessible

Article by Allison Ebner | Graphics courtesy of Sheara Williamson and Eric Greska

Every semester, students face the seemingly inevitable decision: purchase expensive course materials or spend that money on rent and other essentials. When students choose the latter, they start the course without the assigned materials and at an automatic disadvantage.

To remove this barrier to learning, many faculty turn to open educational resources (OER), which are openly licensed, online learning materials that are significantly more affordable or even free. More than just a cost saver, OER materials also enhance students’ ease of access and allow faculty to customize their course materials.

Professors Eric Greska and Sheara Williamson from the Department of Kinesiology and Applied Physiology (KAAP) are among those who have embraced these dynamic learning tools.

“We have to adapt to how students are learning,” Williamson said. “Using an OER resource allows students to access it online. They can download it and even take it mobile. They have access, day one, and they have access forever.”

Greska and Williamson each teach sections of Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology, a course taught every semester that reaches more than 1,000 students a year studying sports health, nursing, health behavior sciences, engineering, biology and psychology.

Before the course redesign, the required textbook for the course cost $250-$300 brand new. Recognizing the problematic pricing and seeking ways to make the course more accessible for students, Greska and Williamson took steps to transition their course materials to OER. When they launched the redesigned course in spring 2020, students could access all of the course materials for just over $30.

To achieve this level of transformation—and savings—required time, effort and support.

Greska and Williamson received a grant from the University’s Reengineering Large Introductory Courses (ReLIC) grant program, which provided them with funding as well as hands-on support from staff at the Center for Teaching and Assessment of Learning (CTAL) and the Library, Museums and Press.

As part of the grant, they attended CTAL’s Course Design Institute, an intensive three-day program that provided them with the framework for redesigning a course by focusing on elements most likely to improve student outcomes. CTAL staff walked them through the process of establishing clear and meaningful student outcomes, and created a course syllabus to match.

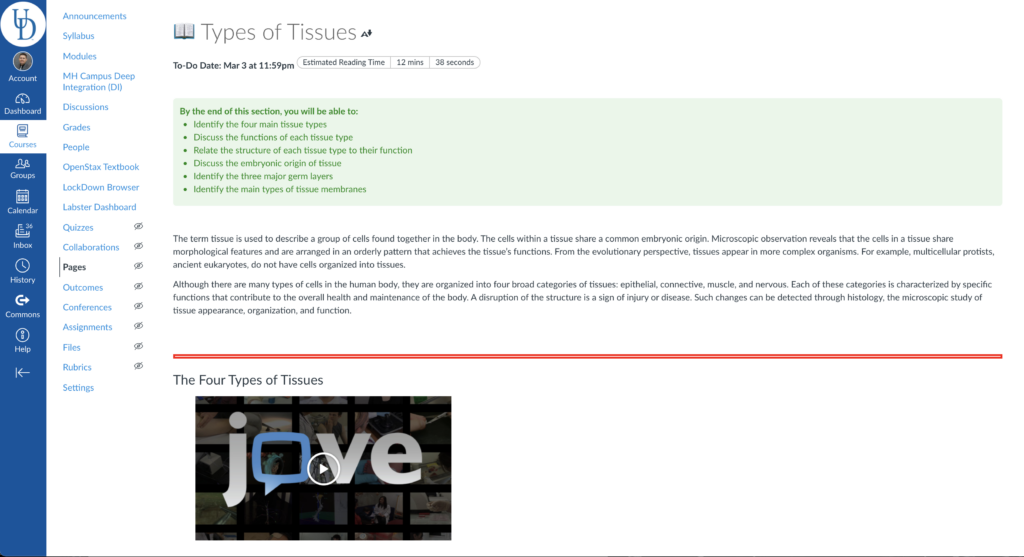

The OpenStax textbook can be ported directly into a Canvas course. Here, we see a glimpse of the Canvas course from Professor Eric Greska’s account. You can see the open textbook copy as well as other embeddable components, like videos.

With this information as their foundation, Greska and Williamson began to identify OER resources that would best support their course goals.

Their first step was adopting the Anatomy and Physiology OpenStax textbook, an open-source, peer-reviewed textbook that is freely available online and in PDF format. (A low-cost print version is also available.) Since OER materials are entirely customizable, Greska and Williamson could select the chapters and materials that aligned with their syllabus once they adopted the textbook.

“If they’re buying this $250 book, my expectation as [a student] would be then we better use every single page, and I better learn every single item,” Greska said. “But with OER, we can pick and choose what we want in there, cutting out the material we normally [skip]. It’s not even there if we don’t want it there.”

In addition to quality text, when it comes to teaching the sciences, faculty also need high-quality images. To find open source images that fit their needs, Greska and Williamson turned to the University’s librarians.

“They wanted to know what our needs were and how they could help us,” Greska said. “[Finding] images was one of the big things that we got a lot of support from Meg [Grotti] and Sarah [Katz] on. We identified that as one of our major hurdles after starting the project.”

Librarians Sarah Katz and Meg Grotti searched a number of open-source repositories for images based on the criteria Greska and Williamson provided. They compiled a list of options for Greska and Williamson to evaluate and determine if they were suitable for their course.

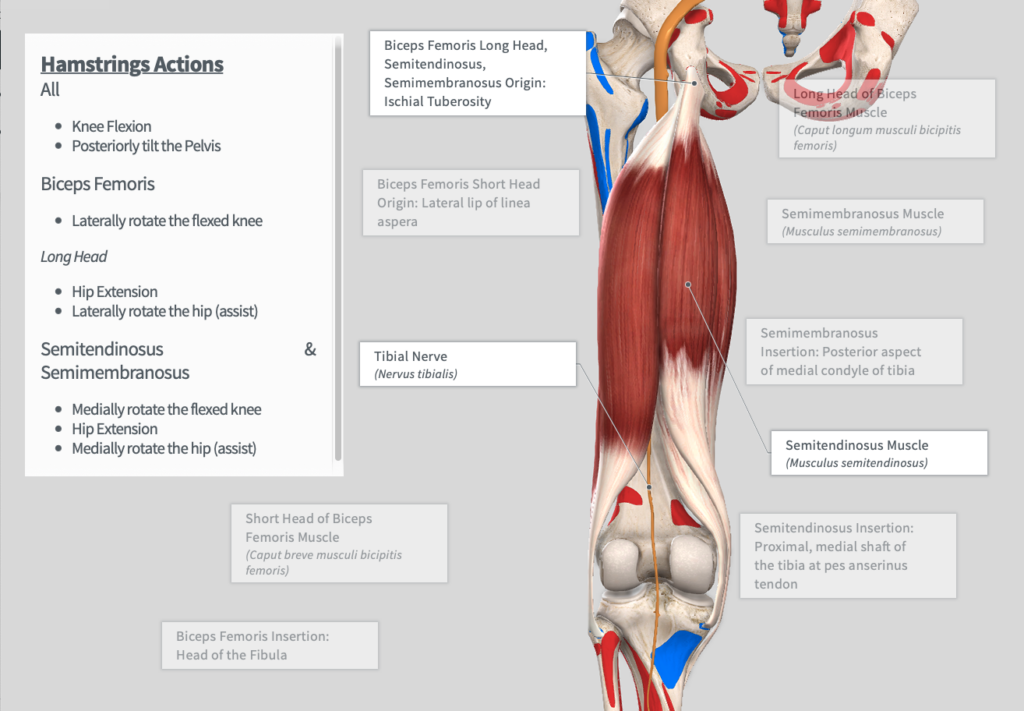

Throughout these conversations on images, Greska and Williamson shared their need for 3D imagery that could serve as a virtual lab for students. While faculty had been using Complete Anatomy—an interactive mobile app that allows users to view and manipulate 12 body systems—Greska and Williamson thought a tool like that would be most powerful in the hands of students.

At the time, the Library had been looking to expand the resources for anatomy and physiology in its collections. When Katz and Grotti learned Greska and Williamson’s course would benefit from Complete Anatomy, the Library was able to purchase a University license for the interactive platform, making it freely accessible to the UD community.

With this tool, students in Greska and Williamson’s course can use their personal devices to interact with images in a 3D environment—think rotating bones for a better view, placing a pin in the image to identify something, and, through augmented reality, even overlaying the 3D image of muscles or organs onto someone in their household. This type of engagement enhances understanding of the material and has been particularly useful during this time of hybrid teaching and learning.

To take the course redesign to the next level, Greska and Williamson incorporated all these newly adopted OER materials into dynamic, interactive assignments within Canvas using a platform called H5P, which the Department of Kinesiology and Applied Physiology funded.

They ported the entire OpenStax textbook into Canvas; embedded images, Complete Anatomy materials and other interactive elements; and created questions, quizzes and homework for students to access in one place. In doing this, they built in low-stakes assignments to encourage students to practice and apply what they’ve learned to the larger, more challenging concepts.

An example of how Professor Sheara Williamson uses the dynamic Complete Anatomy database within her course for enhanced interactivity with and understanding of the material.

“I want [the platform] to be as intuitive as possible,” Williamson said. “And, I’m all about giving them multiple opportunities to practice material so that they’ll remember it. We’re teaching future health care professionals, and anatomy and physiology is foundational material, so if they don’t know it, we’re in trouble. The purpose of my course design is to help them retain material—that’s my main goal.”

For Greska and Williamson, it was a massive undertaking to build the course from the ground up—identifying new materials that met their course goals and presenting them in an accessible and engaging format. However, they’ll be quick to tell you it was a worthwhile effort to create a course that best supports their students.

“We’ve gotten feedback that a lot of students are able to stay on task with [everything] being embedded in Canvas as well as all the other resources we can give them with interactive activities already in there,” Greska said. “The big undertaking we initially had allowed us to really create the course we wanted.”

The launch of the redesigned course during spring 2020 came just in time. In a semester like no other as faculty and students rapidly adapted to teaching and learning remotely, students told Greska and Williamson the course was the easiest for them to transition to online.

“For a very, very low cost, we’re using a lot of materials that are either accessible through our Library or free to download online, and the students are benefiting from that,” Williamson said.

Since the initial relaunch last year, Greska and Williamson have gathered feedback from students about which elements have been most effective and engaging, and which have been overwhelming. With the heavy lifting of a course redesign already in place, they’ve been able to tailor smaller aspects with each semester to make it as helpful and accessible to students as possible.

“Ease of use is a big thing,” Williamson said. “It alleviates some stress that’s associated with the class. The content alone can be intimidating, so if we can present it in a way that relieves that stress—if we have low-stakes activities they can complete to help them remember the material; if they don’t have to worry about affording the textbook or lugging around a heavy textbook; if they can just scroll through the material on their phone—that’s huge. … I don’t see us going back to using a traditional textbook anytime soon.”

With such positive results throughout their experience redesigning the course with OER materials, both Greska and Williamson remain staunch proponents of OER.

This look inside the Complete Anatomy platform highlights the various components of the hamstring, along with their associated actions.

Greska has already implemented Complete Anatomy into a 300-level course he’s teaching, and plans to move the entire course over to OER. With a lab component, the course will likely take two years to switch over all of the materials, but Greska is committed to the cause.

Williamson has also looked to her other courses with OER in mind. Certain subject areas aren’t as robust with OER materials yet. So when Williamson couldn’t find an open textbook she liked for her Introduction to Exercise Science course, she wrote her own, which she plans to publish and make available at low cost. In the same vein as the course she and Greska teach, everything—readings, videos, questions and other interactive components—is accessible from one place.

While Greska and Williamson worked to transition their entire course to OER materials and build an interface in Canvas, they encourage their colleagues to consider smaller options, too. Faculty don’t need to move the whole course to OER at first. They can start with a lecture.

“It’s something that can be taken step by step,” Greska said. “If they’re initially switching over the resources that they’re using to lecture with, then they can look at the entire course next … It is entirely up to them to use what they want and choose other things from other places. It doesn’t all have to come from one textbook. They can pick and choose from different resources to build the resource that they want specifically for their students.”

Whether it’s a single lecture or an entire course, OER materials help to break down barriers to teaching and learning, allowing faculty to have control over the material they teach and students to have more accessible and affordable materials.

Open Educational Resources at UD

During Open Education Week (March 1-5, 2021), the Library, Museums and Press is hosting a series of workshops and panel events designed to introduce faculty and those who teach at the University of Delaware to open educational resources and how such materials can be incorporated into their classes. For more information on OER at UD, visit: library.udel.edu/teaching-and-learning/oer/